Typists who could rattle out a notice on a Remington Portable knew nothing of word wrap. So-called word processors simulated part of the procedure of carriage return by using ‘Return’ keys, now replaced by ‘Enter’ keys on the QWERTY keyboard.

I worked in an office when bound, printed instruction manuals were in their heyday. I didn’t need to read a manual to find out that it was useless either. I could tell from its crisp pages and gleaming cover.

The contents of useful manuals fell at my feet when I took them from the shelf. Company experts on procedures were usually those who wrote, added to, or amended manuals like these.

Many things we now do in the workplace, and the way we go about them, have arisen through the inclusion of the computer. Much of those were modified and re-jigged, or even scrapped from practiced routines and procedures and reinvented, when the use of computer technology became a mandatory part of the processes.

Dissemination of procedural instructions

One of the artefacts that almost disappeared through all this was the printed process specification or business procedure manual. It was sometimes replaced by an online version – less convenient in some ways, more facile in others.

One argument in favour of this replacement was that updates to procedures could be conveyed instantly to a network of workers. In the past these changes were scribbled on the margins of printed manuals and referred to until new versions were published.

But if there is no rigorous and timely procedure for updating an online manual, the user can’t scribble notes in the margins when instructions drift out of date. That is unless they print their own version at some stage. Many do, for this and a number of other reasons. In doing this, however, they may lose touch with subsequent amendments that are only announced on the online version.

Sometimes the business procedure manual, if it existed at all, simply disappears altogether, to be recreated in notes and copies of those made by industrious workers who recognise the need for a manual of some sort. Announcements of new procedures or changes to existing ones sent round by email are filed in either digital or printed form by this diligence.

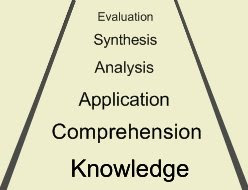

Evolving 'expertise'

Through this process there evolves a wealth of expertise of varying quality. Someone in need of information about a business procedure may skip around a workplace looking for advice from those workers well known for gathering and squirreling away procedural information.

And new ‘experts’ come into being.

This is all very well, until there is a real need for a unified approach to a specific and important procedure. It is a property of communities that exists in large workplaces, that they are recursively elaborate and capricious in how each separate part functions according to its situation.

So what's the solution to communicating unequivocal up-to-date procedural methods of practice to all parts of the workplace?